Work has been incredibly busy lately, and last weekend, I decided to take a break. Getting out for a long hike is therapeutic. I really couldn’t afford to take a day off and indulge this passion of mine, but I new I needed it, even if I would be paying for it later. And so it was that I took last Sunday, March 21st, as a day to indulge myself with the next stage of the Trans Swiss Trail.

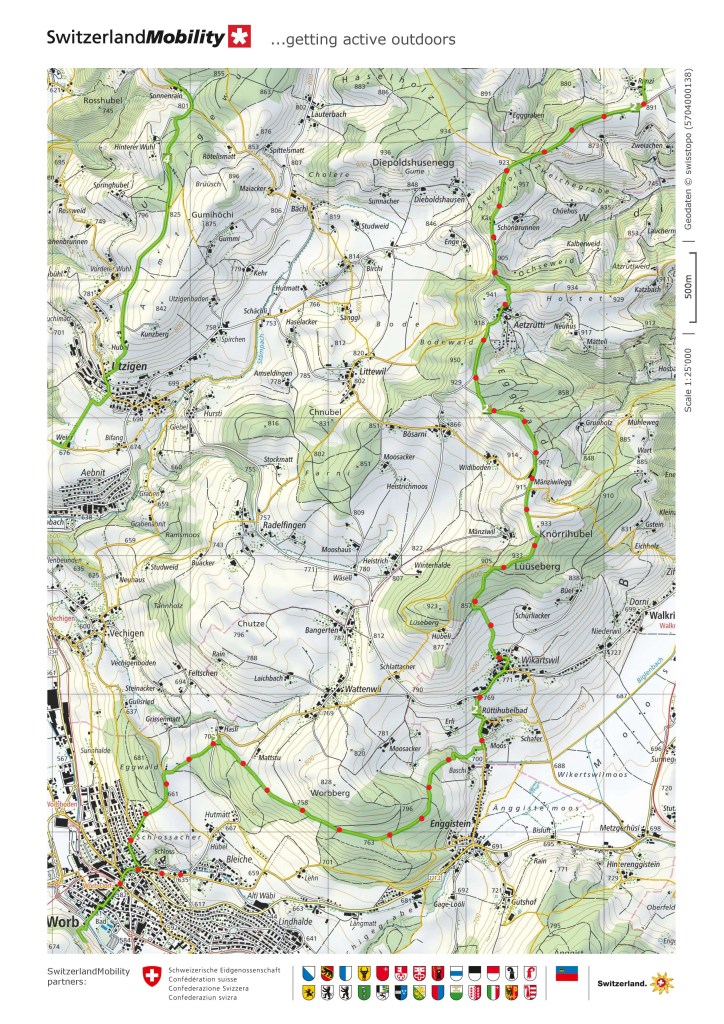

I started out early, and I was in Worb just after eight o’clock. Heading out on the trail, I stopped briefly at the church. It was open. The organist was just setting up for the Sunday services. The church itself is plain. The Swiss Evangelical Church does not go in for a lot of decoration.

I went on from there. I decided to take a short detour to see the local schloss. The schloss, or castle, dates back to the twelfth century. It was renovated and expanded several times over the centuries. After changing ownership a couple of times in the 19th and 20th centuries, it was most recently acquired by the descendants of the original owners in 1985. The schloss is in private ownership, and the gates were firmly shut when I got there. I had to be content with looking in from outside the walls.

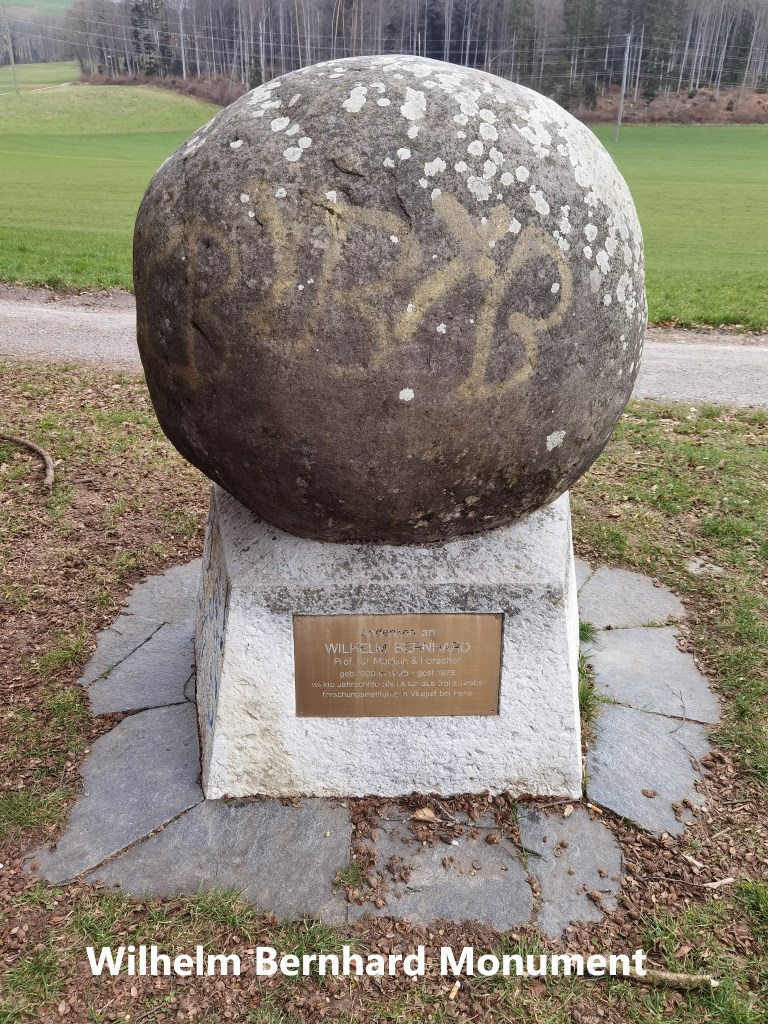

Then I was back on the trail. I headed up out of the town and into the countryside beyond. Just coming into the open fields, I found a monument to Wilhelm Bernhard. Bernhard was the son of a local farmer. He grew up in Worb with an interest in science, getting his doctorate in 1946. He went on to a research institute in Paris in 1947, a time when the new technique of electron microscopy was allowing scientists to see components of living cells too small for conventional microscopes. Through the 1950s and 1960s, Bernhard was one of the pioneers in identifying the structures within the nucleus of cells. He died in 1968. In these days of great advances in genetic science it is easy to forget the pioneers whose earlier advances made so much possible. In the words of Isaac Newton, if we see farther than others, it is because we are standing on the shoulders of giants. Bernhard was one of those.

Going on, I left behind some views of the Alps, and started going uphill into the forest. It would be my last view of the Alps for the day- The trail went on, upwards, first through the fields, and then into the woods. Somewhere just above the 700 metres contour, I was finding small patches of snow, but nothing really significant. And then I was going downhill again, reaching the road a little above Enggistein.

I turned north and the road started going uphill again, quickly coming to Wikartswil. This little village originally started as a tent settlement back in the thirteenth century. It is not considered a community in its own right, being too small, but comes under the governance of the nearby parish of Walkringen.

From Wikartswil, the trail continues uphill, soon going off-road and into the woods of the Lüüseberg. I was back into snow at this stage. It wasn’t the patchy snow that I had seen closer to Worb. But it was old snow, with lots of footprints, crisp from days of sunshine with nights of frost. Such snow makes for good walking, and I was soon at the Knörrihubel. A single small tree tops this mount, looking all the more lonesome for being in the snow, without a single leaf.

The route is fairly flat all the way from Knörrihubel to the little hamlet of Aetzrütti. There was still plenty of snow on the surrounding fields and woods, but the roads were clear. At times, the views over the landscape showed the struggle between Winter and Spring, seemingly with neither fully in control. There is an inevitability about the seasons, and I know that Spring will win out soon. The local people know that too, and I could see Easter decorations on some houses.

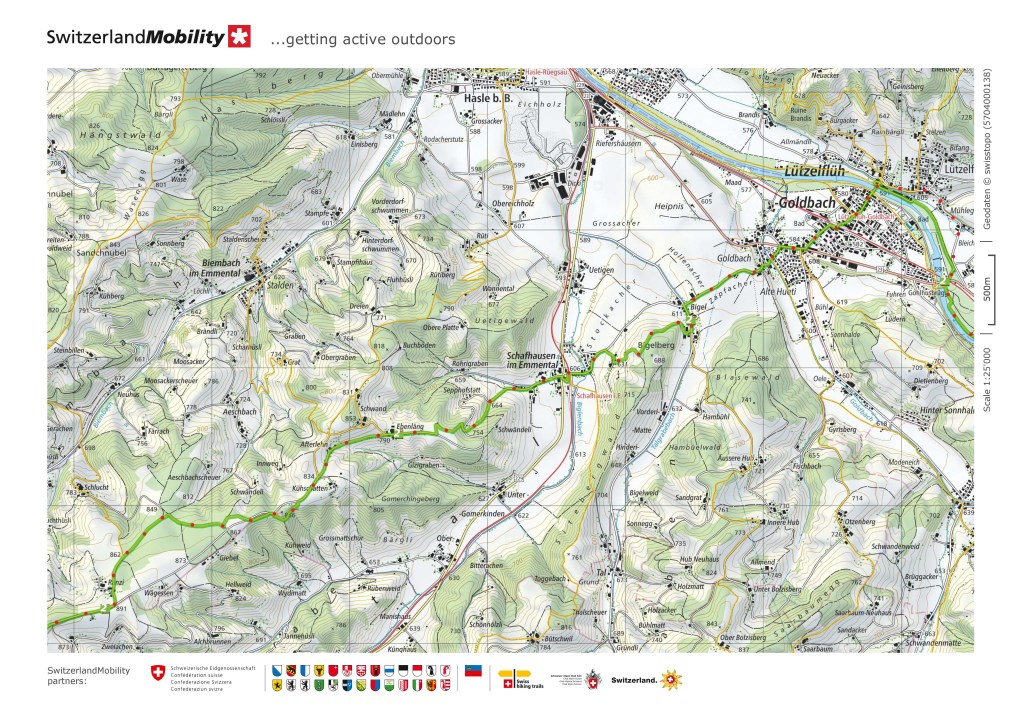

After Aetzrütti, the trail goes through a mixture of woodland and pasture before eventually descending towards the Emmental. The Emmental is farming country, especially dairy, and several farms had signs offering produce for sale. I stopped at one and got some local cheese. It works on an honour system. There is a fridge containing the cheese outside the house along with a box to put the money in. The Swiss have a mutual respect for each other, and I suspect that defaulters on such a system are few.

I went on through Afterlehn and Ebenläng, downhill all the time, and soon Schafhausen im Emmental came into view.

Schafhausen is a small village of prettily decorated Bernese houses, sitting at this branch of the main Emmental. In these days when everything is closed, I didn’t stop but went on over the hill towards Lützelflüh. Coming down into the hamlet of Bigel, I was sure I could here an alpenhorn in the distance, clear enough to be sure it was there, but too faint to know where the sound was coming from.

I went on through the town of Goldbach and crossed the Emme to reach Lützelflüh itself. The church in Lützelflüh dates back to the nineteenth century. It was closed unfortunately, so I cannot comment on the church itself. But in the churchyard, on the south side of the building are the graves of three people considered important in Swiss literature of their time. Jeremias Gotthelf was the pen name of Albert Bitzius, and it is by that pen name that he is remembered. Bort at the end of the eighteenth century into a Bernese patrician family, he became the pastor for Lützenflüh in 1831. His novels are set in the Emmental, and his work is considered important not only in terms of Swiss literature, but German language writing of that time. The other two, Emmanuel Friedli and Simon Gfeller were prominent in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Unlike Gotthelf, they came from poorer families around Lützenflüh. Gfeller was a teacher in the town for thirty years from 1887 and wrote several books about life in the area. Friedli was pastor in the town but his re-election as pastor was refused in 1896. He turned to writing in the years that followed. His literary work focused on the folktales of the area, and he even compiled a dictionary to link the local dialect with high German. All three, Gotthelf, Gfeller, and Friedli, are buried side by side. It is interesting that one so small a town could give so much to Swiss literature.

From the church, I made a small detour, leaving the trail to take in the Kulturmühle. This is a former mill, now turned into a cultural centre for the town. Like so much else, it was unfortunately closed. The mill has its own little covered bridge over the millstream, and the millwheels are still turning in the water flow

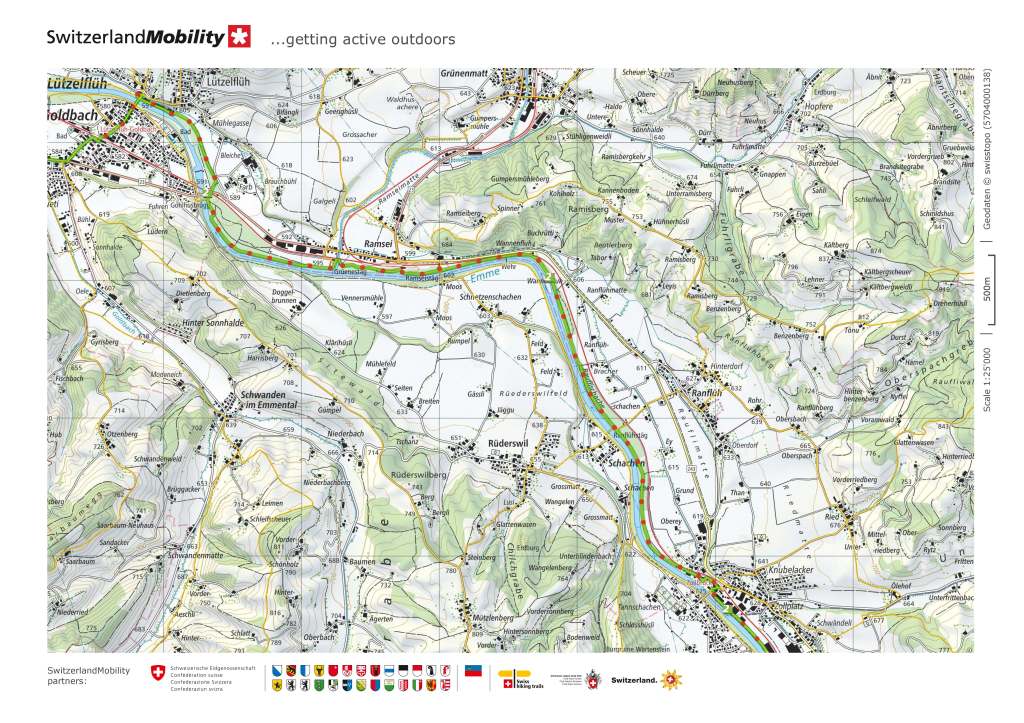

Back on the trail again, I was to follow the Emme upstream. The Emme rises in the Bernese Oberland and flows for about eighty kilometres to join the Aare. It is normally a gentle river, but is noted for the variability of its flow. Jeremias Gotthelf in one of his books describes a catastrophic flood on the river in 1837. To control the water flow, the river has numerous weirs.

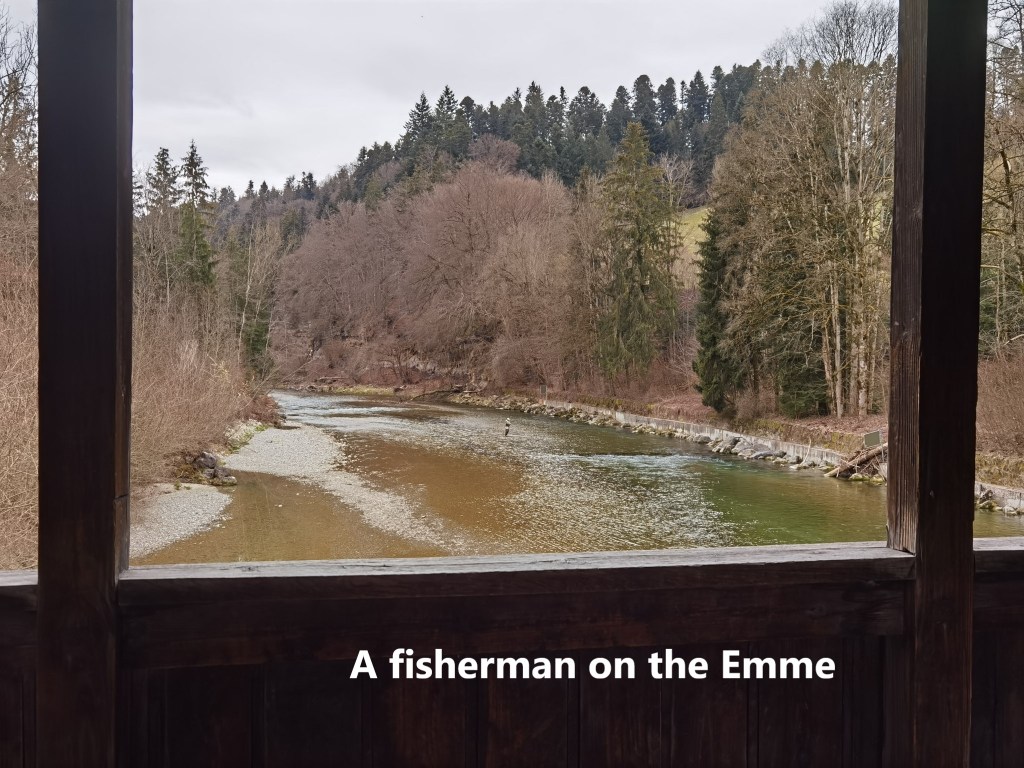

Looking at the Emme as I walked along, it would be hard to believe that the river could ever be destructive. I came to a covered bridge just on the edge of Lützelflüh. Looking from the bridge, I could see a man fishing, casting flies to attract the fish. There can be few activities more tranquil. I know that such fishing requires skill and patience. But I am a wanderer, and I went on my way.

Leaving Lützelflüh behind, my route continued on. From there it is a gentle walk. The trail stays close to the river, going first eastwards, and then turning in a generally southerly direction. It remains a tranquil setting all the way to Zollbrück, which was my destination for the day.

It has been an interesting walk, and I accumulated 45,432 steps in the day.